Member-only story

Why Our Brains Want to Spread Misinformation

Even when it’s banal or harmless, this is why we can’t help spreading false information

The other day, I came across a cute little video. It is a monkey playing a memory game incredibly well. Way better than I ever could. Underneath is an explanation: “Millions of years ago,” it says, our ancestors “lost a tremendous amount of short term memory,” which we replaced with different brain material. “But why? So we can — talk.” The conclusion is that chimpanzees, who haven’t made that sacrifice, can accomplish amazing feats of memory but we, who have, can’t.

It is one of those conclusions that is surprising and kind of delightful. I’m tickled by the idea that ancient humans swapped one part of their brain for another, like making space in a cupboard. I watch a few seconds of the monkey tapping away at the memory game and then I scroll on. (The video is two and a half minutes of a monkey tapping a screen. Who has that sort of time these days?)

A few weeks later, while talking to some friends, the topic of short term memory comes up and I mention the chimpanzee. I search through Twitter to show them the video. But instead of finding the original tweet, I come across one in which an evolutionary anthropologist is referring to it. “This debunked finding keeps coming back,” it says, “Humans are at least as good at this task as the chimpanzees. It’s a practice effect.”

Since everyone is waiting to see the monkey video, I gloss over this and play the video. “Um, some people think that actually with practice we might be good at this too,” I say lamely. It feels a bit wrong, having brought the monkey up, to immediately fact-check myself and spoil the fun. So we watch the video. And then we carry on with our lives.

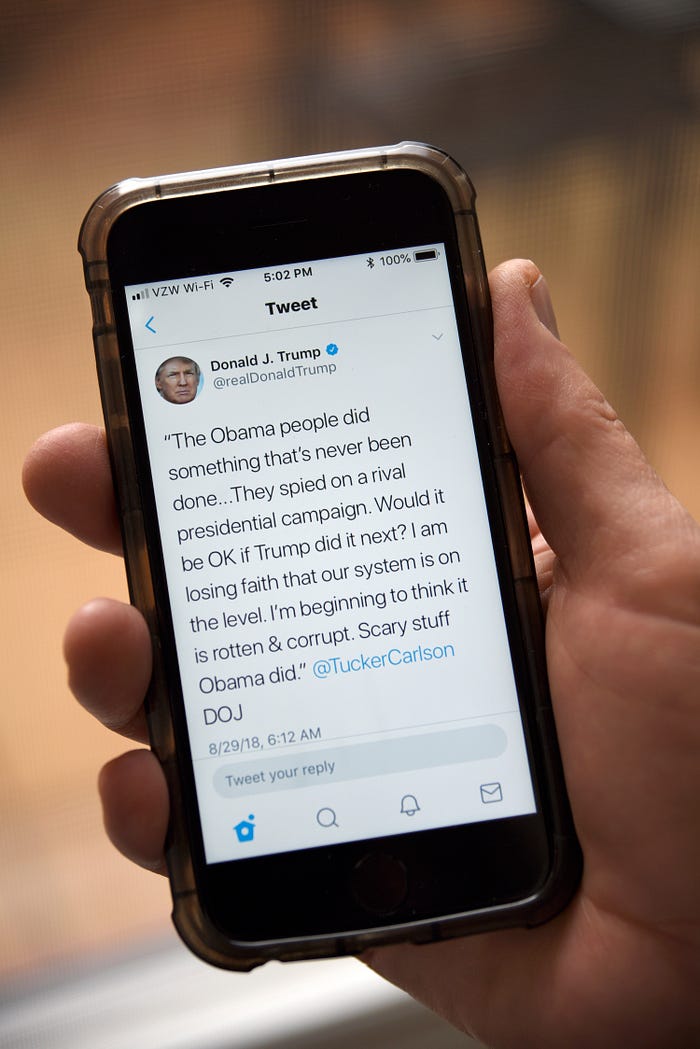

The tweet containing this “fact” has over 100,000 likes and has been seen 3.1 million times. The message explaining it is untrue has 339 retweets.