Member-only story

Here’s an Ethical Open-Source Alternative to Alexa

Why I gave my voice to Mycroft A.I.

When I was young, my parents gave me cassette tapes of old-time radio broadcasts to listen to. One of my favorites was a 1948 episode of Quiet Please. In “The Pathetic Fallacy,” an engineer named Quinn brags (in glorious ’40s tech-speak) to a pair of journalists about the giant computing machine that his organization has constructed:

When I was young, my parents gave me cassette tapes of old-time radio broadcasts to listen to. One of my favorites was a 1948 episode of Quiet Please. In “The Pathetic Fallacy,” an engineer named Quinn brags (in glorious ’40s tech-speak) to a pair of journalists about the giant computing machine that his organization has constructed:

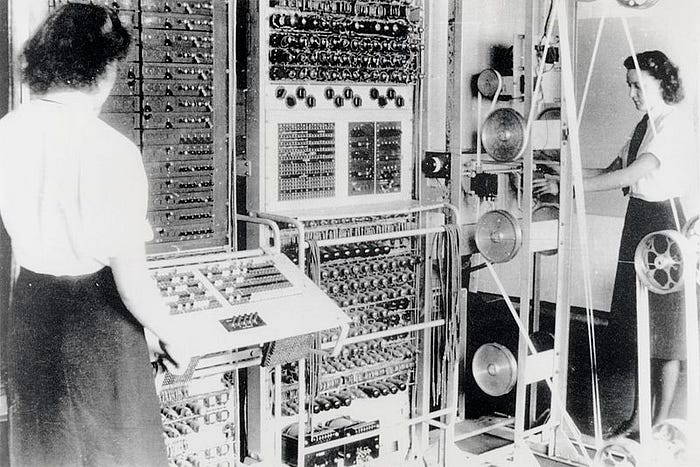

The actual machine is behind those walls. Three rooms full of tubes and motors and stroboscopes and several thousand miles of wiring and some devices that are not public property yet. The machine took six years to build, and a total of eighty-one expert technicians were employed continually during that time. So you can understand that any one man knows very little about the actual construction of this giant, mechanical brain.

Quinn’s fortunes plummet when he realizes that “the machine” has become self-aware. It has grown angry with him. It can speak. It sabotages his career until he almost changes his name and flees into hiding. Finally, we learn that the machine, a mighty assemblage of gears and motors, is in love with Quinn and only desires his love in return.

The talking machines of today are small by comparison but are every bit as disruptive and incomprehensible as “the machine” of my childhood radio drama. As with video calls and virtual reality, digital assistants have completed the transition from the stuff of ’40s science fiction to a banal, almost innocuous standard. Like the machines of old, digital assistants occupy many rooms. They perch on our bedside tables, mingle with the paper towels on our countertops, and crouch beside our televisions. An expected 1.8 billion digital assistants will be in homes and offices by 2021, listening patiently to our voices and trying to help their companies to understand our thoughts and desires.